I have noticed that more and more people are using the term "structured data" to refer to XBRL-based financial reports. I certainly buy into that term. However, I tend to prefer the term XBRL-based digital financial reporting. Same idea though.

The "structure of the data" is a representation of the information. Far too many people make what I consider to be a mistake of using the term "tag" to describe the stuff within an SEC XBRL financial filing. I consider this to be a mistake for two reasons.

First, "tag" is too general a term. What many people refer to as a "tag" could be a Table, an Axis, a Member, a LineItems, a Concept or an Abstract. For example, if you go to the US GAAP XBRL Taxonomy (2014 version) schema and you query that schema using your favorite XML parser and the following XPath expression: //xs:element[@substitutionGroup='xbrldt:hypercubeItem']. You get exactly 301 hits, each which represents an XBRL hypercube or what the US GAAP XBRL Taxonomy calls a [Table]. Do the same thing with this XPath //xs:element[@substitutionGroup='xbrldt:dimensionItem'], and you get 327 hits, each representing an XBRL dimension or what the US GAAP XBRL Taxonomy refers to as an [Axis]. Do the same thing with the XPath //xs:element[@type='nonnum:domainItemType'] and you get 1802 [Member]s.

It starts to get a little trickier because of how the pieces are structured to get the [Line Items], the [Abstract]s and the Concepts. The point is, the 17,433 individual elements (this XPath //xs:element) can be grouped into specific categories.

Those categories of things play different roles in representing the structure of an XBRL-based digital financial report. In another blog post I pointed out that SEC XBRL financial filings use these structures very consistently. That is to be expected, because XBRL enforces many of these constraints as to how the pieces which make up the structure can be used. The XBRL definition relations have to be created very precisely and if you make a mistake, XBRL validation will point out that mistake.

Representing these structures using XBRL presentation relations is a little different. There are no real rules enforced by XBRL as how to represent information using XBRL presentation relations other than you have to follow a very general "parent-child" type hierarchy. Some SEC EFM rules apply additional constraints to the presentation relations saying that the presentation, calculation, and definition relations need to be consistent.

But the rules are still not strong enough to keep things consistent and therefore can cause potentially confusing representations of the information.

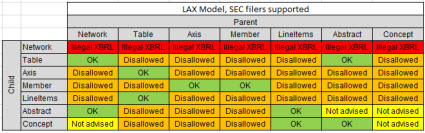

The matrix below summarizes relations which make sense and are "OK", relations which don't make sense and are therefore "Disallowed", and for relations which don't really hurt anything but really don't make sense are "Not advised". Also, note that 99.99% of all relations in SEC XBRL financial filings follow this pattern.

The way to read the matrix is that the columns contain the parent structure category, the rows contain the child structure category, and the intersection cell specifies whether the relation is allowed or OK. For example, a Table can have exactly two types of children: Axis or LineItems.

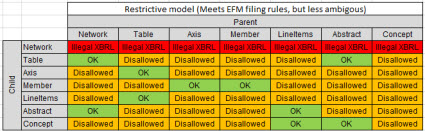

This screen shot shows a more restrictive matrix. This causes even less potential for ambiguity and would still meet all the SEC EFM rules:

Here is an example of a more restrictive rule: What would you ever represent which would call for an [Abstract] to be the child of a Concept? Personally I cannot think of any reason. In fact, of 3,165,249 parent concepts in the a set of 6,674 SEC XBRL financial filings, only in 546, which is .000172% of the time, did someone feel the need to express this sort of relation. That fact alone is ample evidence that my reasoning is correct.

Why is all this important? Why are you telling me the obvious, the following categories of report elements exist in SEC XBRL financial filings: Network, Table, Axis, Member, LineItems, Abstract, Concept? If 99.99% of people already follow these rules, why is this important?

The answer, which I will build on in subsequent posts, is that this is just the beginning and there are way, way more structures. Member arrangement patterns and concept arrangement patterns are two other examples.