Machines can do things to help humans create or use digital financial reports. This help from machines will reduce costs and increase quality. How? Exactly how do you make financial report creation applications smart?

Simple. The first thing you have to do is realize that many of the work practices accountants use today will not be the work practices accountants will use in the future. What if you take the knowledge related to financial reporting, you put as much of that knowledge as possible into machine readable form, and then build software which can make use of that knowledge to assist the users of that software tool in creating financial reports.

Sound odd? Sure, it sounds odd to professional accountants who have been creating financial reports using first paper and typewriters, then paper and word processors, then paper and word processors outputting electronic formats such as PDF and HTML. Work practices will change.

But when you really think about it and realize that Microsoft Word (which is used to create about 85% of financial reports) and Microsoft Excel (which is used to accumulate, aggregate, and organize the stuff that ends up in Microsoft Word) don't understand anything about financial reporting, you can see the opportunity.

Hypothetically, let us say that you wanted to do this. (We will ignore the fact that people are already predicting that this will happen, that the global standards to do this efficiently already exist, software vendors already seem to be doing pieces of this, and that other domains such as health care are working toward this same goal.) How would you do it?

The key is machine readable knowledge with high semantic clarity, making sure the software truly understands financial reports and that users of the software agree that the software understands financial reports and creates those financial reports correctly. How do you achieve that?

First off you have to realize that a machine cannot do everything. Some things are objective and other things are subjective, requiring human judgement. Machines will not do the things that require judgement, humans will still perform those tasks. Machines will take care of the objective tasks, the tasks which can be effectively performed by a machine such as a computer.

So how do you do this and how do you make sure you have high semantic clarity? Here is the summary:

- Classification system: You will need some sort of classification system. Some classification systems are more expressive than others. The classification system should be flexible or extensible because financial reports are not forms. The classification system should be a global standard so that the classification system can be shared as broadly as possible to keep the costs of creating and maintaining the classification system within reason.

- Syntax: You will have to express the information in the classification system you come up with in some machine readable syntax. Some syntaxes are more expressive than others. Some are more flexible than others. Is the syntax a global standard or proprietary? A global standard would be preferable.

- Business rules: You will need to express the business rules of the domain as completely as possible so that (a) people understand and agree on those business rules and (b) information can be validated against those business rules to make sure the information created is correct. Both of these work together to make sure financial reports are created correctly.

- Interoperability: No one business system can do everything that is necessary. You will want to leverage business rules and other metadata from other systems so interoperability is important. This will help keep costs down. One of the problems with software today is that the software is centered on itself, not on the user or what the user needs to do. What if software were truly user centric or task centric? What if all the resources used to create a financial report were available within the same software application? The Accounting Standards Codification (ASC), GAAP guides, disclosure checklists, audit guides, accounting trends and techniques, etc. What if all these things were not human readable things, but things that were both machinge readable and human readable. What if you had an integrated "Chat" window where you could ask for advice from a professional. What if you could get on-demand training on a topic you had not yet been exposed to. I could go on and on.

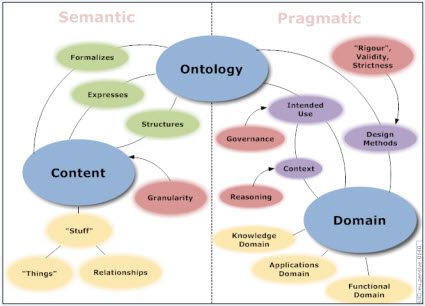

A domain classification system can be on the formal side, or on the informal side. Achieving the appropriate balance is important. This graphic from the Ontology Summit provides a sense of this

From An Intrepid Guide to Ontologies http://www.mkbergman.com/date/2007/05/16/

From An Intrepid Guide to Ontologies http://www.mkbergman.com/date/2007/05/16/

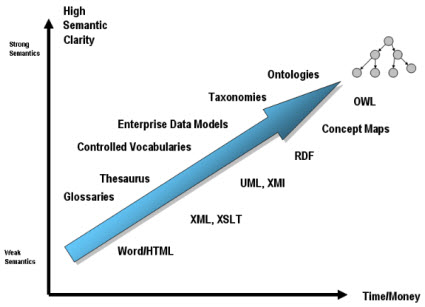

The graphic below based on work by Leo Obrst of Mitre as interpreted by Dan McCreary shows the trade-off between semantic clarity and time/money required to obtain that semantic clarity:

From An Intrepid Guide to Ontologies http://www.mkbergman.com/date/2007/05/16/

From An Intrepid Guide to Ontologies http://www.mkbergman.com/date/2007/05/16/

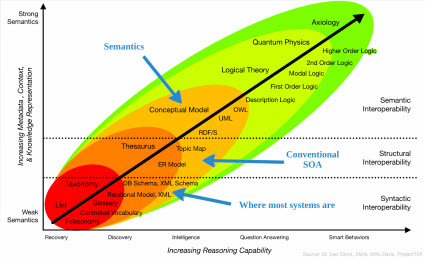

This second graphic, similar to the graphic above from the Semantics Overview, adds the syntactic, structual, and semantic interoperability into the equation and changes the "Time/Money" axis from above into the "Reasoning capacity" axis:

Semantics Overview http://prezi.com/prwsxj8po3ln/semantics-overview/

Semantics Overview http://prezi.com/prwsxj8po3ln/semantics-overview/

What is really encouraging is that even without the approprite software tools, accountants creating SEC XBRL financial filings are getting a high level of reported information correct when evaluated against a set of seven criteria. Admittedly these criteria do not exercise the entire digital financial report. But it is a start and provides both a beach head to start with and a framework to work within. A roadmap would be very helpful. Clearly quality needs to grow to a level of 99.9% or better if that is possible. Learning from SEC XBRL financial filings will help strike the appropriate balance.