BLOG: Digital Financial Reporting

This is a blog for information relating to digital financial reporting. This blog is basically my "lab notebook" for experimenting and learning about XBRL-based digital financial reporting. This is my brain storming platform. This is where I think out loud (i.e. publicly) about digital financial reporting. This information is for innovators and early adopters who are ushering in a new era of accounting, reporting, auditing, and analysis in a digital environment.

Much of the information contained in this blog is synthasized, summarized, condensed, better organized and articulated in my book XBRL for Dummies and in the chapters of Intelligent XBRL-based Digital Financial Reporting. If you have any questions, feel free to contact me.

Entries from October 1, 2014 - October 31, 2014

Taxonomies Cannot be Open, But they Can Provide Openings

This blog post is a reorganized version of a message I posted to the XBRL-public discussion group.

A year or so ago in a blog post I tried to explain the difference between an "open" taxonomy and a "closed" taxonomy. Someone pointed out to me, correctly so, that it is systems that are open or closed and that taxonomies always must be closed.

The XBRL International Taxonomy Guidance Document now uses these terms. What this really boils down to is the use of XBRL's extensibility. The desired goal here is to employ that extensibility effectively.

I believe that I can better articulate system dynamics now, this blog post is an attempt to do so. First though it is important to keep in the back of your mind the purpose of a system. I am speaking of systems such as XBRL-based public company financial filings submitted to the SEC which does employ extensibility. This is how I articulate the purpose of such a system:

Prudence dictates that using financial information from XBRL-based public company financial filings to the SEC should not be a guessing game. Safe, reliable, predictable, automated reuse of reported financial information by machine-based processes seems preferable.

Taxonomies MUST ALWAYS be "closed" or rather have conscious, known, understandable boundaries. Or more precisely, a taxonomy provides specific, conscious "openings" where those reporting against the taxonomy can consciously articulate specific information and therefore extend the taxonomy in conscious, known, specific ways ONLY. A machine-based system can tolerate zero ambiguity.

This is NOT to say that extensions cannot be employed. The FDIC system is successful because they matched the system and the taxonomy. The FDIC reporting system is "closed". The FDIC uses forms. Many others implementing XBRL "retreat" to this approach because they don't understand how to make XBRL's extensibility work or they believe that it cannot work so they don't bother to attempt to employ it.

The SEC use case is open reporting. US GAAP-based financial reporting is open, it is not a form. It is important to understand the difference between two terms at this point: arbitrary and standard.

- Standard: used or accepted as normal or average; something established by authority, custom, or general consent as a model or example

- Arbitrary: based on random choice or personal whim, rather than any reason or system; depending on individual discretion (as of a judge) and not fixed by law

US GAAP is not arbitrary, it is standard. A mistake the FASB made in creating the US GAAP XBRL Taxonomy and that the SEC made in defining the Edgar Filer Manual (EFM) rules is not establishing appropriate boundaries or specific, conscious "openings". To some, the system looks totally open and even random.

The external financial reporting managers of the public companies who file with the SEC know the rules of US GAAP. There is zero tolerance for error with respect to conformance with US GAAP. Now, with respect to XBRL-based digital financial reports conforming to US GAAP is hard right now because there are thousands of details that must be complied with but neither the FASB nor SEC provided those business rules which enables a machine to help external financial reporting managers conform. But that is changing. The market is providing the necessary machine-readable business rules. This can be seen by following the increasing conformance to the fundamental accounting concept conformance rules.

But there are two other missing "layers" of business rules relating to expressing financial information using XBRL-formatted information.

One missing layer is the notion of a machine-readable business report model. XBRL has an explicit business report model. In fact, XBRL has two explicit business report models which is part of the confusion when one attempts to understand the semantics of the model. There is one model expressed by the XBRL 2.1 technical specification. There is another model, built several years later, expressed using XBRL Dimensions 1.0. The people who created the XBRL Formulatechnical specification defined what amounts to an "aspect" based business report model can be used with both the XBRL 2.1 and XBRL Dimensions models. The people who wrote the XBRL International Abstract Model 2.0 also defined a model which tries to reconcile all of these different models into one business report semantic model.

This model is not "negotiable". These are technical specification all of which have conformance suites which ensures software interoperability. Arbitrary interpretation of the model is not allowed, the model is a standard. In fact, over 99.9% of the relations within XBRL-based filings conform with this report level semantic modelbecause the software they use REQUIRES them to comply because of those conformance suites. Some software does not comply and therefore you get external financial reporting managers who put a [Member] within a set of [Line Items] which makes zero logical sense. Now XBRL 2.1 allows that believe it or not, XBRL 2.1 has no knowledge of XBRL Dimensions. But XBRL Dimensions does NOT allow this and these rules are even enforced by the XBRL Dimensions specification.

Confusing? Yes, I understand. The US GAAP XBRL Taxonomy makes this even more confusing by using both the XBRL 2.1 model (no dimensions) and XBRL Dimensions (with dimensions) in the same taxonomy.

I articulated this business report model: Financial Report Semantics and Dynamics Theory. This helped me to sort through all of these moving parts and it has helped others to do the same. Further, I proved that 99.9% of SEC XBRL financial filings conform to this model.

So, a mistake the FASB and therefore the SEC (who uses the US GAAP XBRL Taxonomy created by the FASB) is making is that this business report model is not clearly articulated. In fact, the model is misunderstood and even abused. External financial reporting managers, given inappropriate guidance from others, are using the business report model somewhat like a presentation dart board. For example, anyone who puts a "Class of Stock [Axis]" on a balance sheet is misunderstanding this model. What they are saying is that "Cash and cash equivalents" has a characteristic that it does not have.

Dimensions articulate characteristics. Go to section 1.3 of the XBRL Dimensions specification which defines the term "dimension":

Dimension: "Each of the different aspects by which a fact MAY be characterised."

OK, so the question that raises is what is the definition of a characteristic. This is my definition of characteristic:

Characteristic: A characteristic describes a fact. A characteristic or distinguishing aspect provides information necessary to describe a fact or distinguish one fact from another fact. A fact may have one or many distinguishing characteristics.

Don't like my definition? Please point me to the FASB or SEC definition.

Reality is pretty clear and if a little common sense is employed, understanding this is rather straight forward: Cash and cash equivalents, Receivables, Inventory, Accounts payable, Long-term debt, Equity, don't have a class of stock [Axis] because they don't have that characteristic. If you want to break down common stock or preferred stock and you want to use an [Axis], you have to do it in another [Table].

So that is a mistake the FASB/SEC made: not clearly articulating the business report model and therefore rather than the one standard interpretation of the model, you get each external financial reporting manager, software vendor, etc. using their arbitrary interpretation of the model. That will not work.

A second mistake the FASB made is that they did not complete the US GAAP XBRL Taxonomy according to things articulated in the US GAAP Taxonomy Architecture. The notions of "extension points" and "extensibility rules" and "concept arrangement patterns" or patterns were all articulated in the US GAAP Taxonomy Architecture.

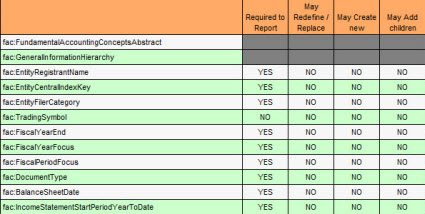

I understand extension points and extensibility rules because I was one of the authors of the US GAAP XBRL Taxonomy architecture. You can understand what "extension point" and "extensibility rules" are all about by looking at a few examples provided in this graphic:

(Click image for full graphic)

(Click image for full graphic)

The graphic shows the fundamental accounting concepts broken down into groups:

- Concept REQUIRED. For example, dei:DocumentPeriodEndDate is a REQUIRED concept

- Concept MUST NOT be redefined or replaced. For example, "Current assets" CANNOT be redefined or replaced.

- Concept MAY be redefined. For example, NONE of the fundamental accounting concepts can be redefined.

- Concept MAY have a new child concept (subclass) created. For example, the concept "Cash and cash equivalents" can have a new subclass created such as "Petty cash".

The point is, concepts and relations between concepts act differently. The US GAAP XBRL Taxonomy treats every concept and relation pretty much the same.

Finally, part of the "extension point" and "extensibility rules" part is the notion of a "class" and "subclass". What I have discovered is that the rules necessary to provide the approprate boundaries and points of extneion go something like this:

- Concept has class: Every concept defined needs to be associated with some fundamental class.

- Don't cross classes: Filers MUST NEVER "cross classes", they cannot redefine the meaning of a class by using one class as part of another class. An example of this is how AT&T redefined operating expenses to include direct costs of sales. Filers MUST NEVER do this. Besides, the concept "Costs and expenses" already does that. Another example is filers redefininginterest and debt expense to be part of nonoperating income (expenses). A simple solution, if that is allowed, is to add a concept to the US GAAP XBRL Taxonomy "Nonoperating income (expense) including interest and debt expense.

- Associate EVERY extension with some class: Filers MUST be required to associate every extension that they create with some existing US GAAP XBRL Taxonomy class. This is not something the FASB does, but they could articulate this in their architecture. The SEC could do this, and MUST do this to make the system work correctly.

- Required totals/subtotals: I don't quite understand how to articulate this properly yet, but it goes something like this. Certain specific totals and subtotals MUST be explicitly reported. The reason is, if a machine has to impute (imply) missing values; the value is so essential that if it does not exist, there is a possibility that an error made by a creator of this information can be misinterpreted by a machine-based process and the filer error can mask an impute error. (This blog post explains the details of this, I have not totally figured this out yet)

And so, a taxonomy is never really "open" per se. A taxonomy provides specific "openings". The taxonomy enables those that report against the taxonomy known, understood openings which they must comply with. Those openings provide the system boundaries. Systems MUST have boundaries.

The FASB and SEC need to establish and communicate the appropriate boundaries via the specific openings they allow. They also need to clearly articulate and utilize the standard business report model articulated by the XBRL technical specifications. Arbitrary interpretation of the standard model will never work.

Example of Problems Caused by Forcing a Machine to Imply

This is probably one of the best examples of the problems caused when a machine is forced to imply information. It is an example of where one error can lead to another error which masks the first error. It is also an example of the consequences which occur when a filer in essence redefines the meaning of a concept by using a concept in a different way than it was intended.

I will use this AT&T filing to make my point. I am not picking on AT&T, it is just that I happen to run across this in my tuning of the fundamental accounting concept impute rules.

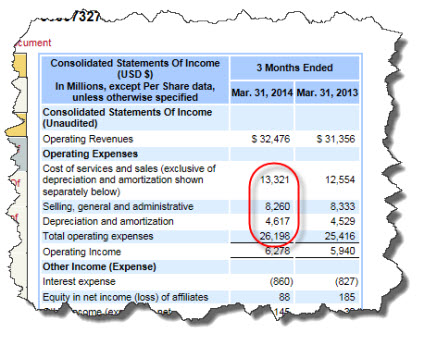

If you look at the income statement of AT&T, focusing on the operating income section:

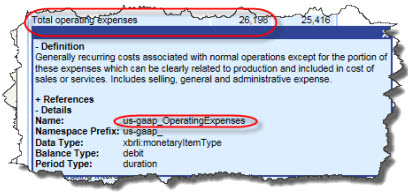

The income statement looks straight-forward enough. Note the line item "Total operating expenses". If you examine the concept using the SEC interactive data viewer, you see that the filer used the concept us-gaap:OperatingExpenses to represent that fact:

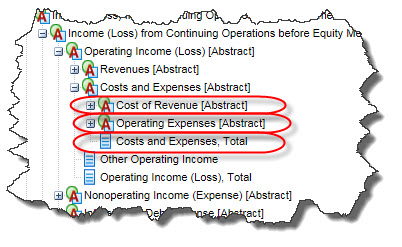

However, if you examine the US GAAP XBRL Taxonomy, you notice that the concept Operating Expenses does not include Cost of Revenue. The total of Cost of Revenue and Operating Expenses is the concept Costs and Expenses:

However, if you take a look at the AT&T income statement again, AT&T included the line item "Costs of services and sales" within the line item Total operating expenses.

So, the problem is that AT&T should have used the concept us-gaap:CostsAndExpenses to represent the line item they refer to as "Total operating expenses". While the label is similar to the concept they did use, the meaning of what they are representing matches the concept Costs and Expenses which includes Cost of Revenue.

The problem is that my fundamental accounting concept relations conformance testing did not pick up this error. The impute algorithm imputed a value incorrectly. So, the error made by the filer who used the wrong concept is masked by an error in the impute algorithm which imputed a value incorrectly. The results of my validation report did not show any errors.

But I found this when I looked at the validation report. Now, a human can figure out that an error occurred by looking at the information, but a machine stumbles over this and does not realize that it made an error. But if I never happend to look at the report, I would not detect the mistake.

This is why it is better to explicitly provide information rather than force a machine to try to imply a fact.

Reading List for Professional Accountants Trying to Understand Digital Financial Reporting

XBRL International released a document, XBRL Taxonomy Guidance Document, which is a very good step in the right direction when it comes to building XBRL taxonomies. The focus is using the XBRL technical syntax correctly. That is only a portion what a taxonomy author needs to understand when they are representing information about a business domain in machine-readable form.

Over the years I have run across the following books which are extremely helpful in trying to understand digital financial reporting. I strongly recommend that for anyone who wants to understand digital financial reporting well or who want to build rock-solid products/solutions to read the following books:

- Data and Reality, by William Kent: (First and last chapter are best, entire book is useful) The primary message of the Data and Reality book is in the LAST CHAPTER, Chapter 9: Philosophy. The rest of the book is EXCELLENT for anyone creating a taxonomy and it is good to understand, but what you don't want to do is get discouraged by the detail and then miss the primary point of the book. It provides something useful. The goal is NOT to have endless theoretical/philosophical debates about how things could be. The goal is to create something that WORKS and is USEFUL. A shared view of reality. That enable us to create a common enough shared reality to achieve some working purpose. Actually SEEING it work (i.e. prototype) PROVES that it works, let you see and understand HOW it works, and help one see how to make it work even better.

- Everything is Miscellaneous, by David Wenberger: (Entire book is useful) This is very easy to read book that has two primary messages: (1) Every classification system has problems. The best thing to do is create a flexible enough classification system to let people classify things how THEY might want to classify them, usually in ways unanticipated by the creators of the classification system. (2) The big thing is that it explains the POWER of metadata. First order of order, second order of order, and third order of order.

- Models. Behaving. Badly., by Emanual Derman: (First half of the book is useful) If you read the Financial Report Semantics and Dynamics Theory, you got most of what you need to understand from this book. But the book is still worth reading. It explains extremely well how it is generally one person who puts in a ton of work, figures something out, then expresses extremely complex stuff in terms of a very simple model and then thousands or millions of people can understand that otherwise complex phenomenon.

- Semantic Web for the Working Ontologist, by Dean Allenmang and Jim Hendler: (First two chapters) This is an extremely technical book, but the first chapter (only 11 pages) explains the big picture of "smart applications". It is awesome. It also explains the difference between the power of a query language like SQL (relational database) and a graph pattern matching language (like XQuery). Querying can be an order of magnitude more powerful if the information is organized correctly. That is why picking the correct data storage format is important.

I would recommend reading the books in the order listed. The investment in time to understand this information will avoid going down the wrong path.

Public Company Conformance to Fundamental Relations Grows to 61.9 Percent

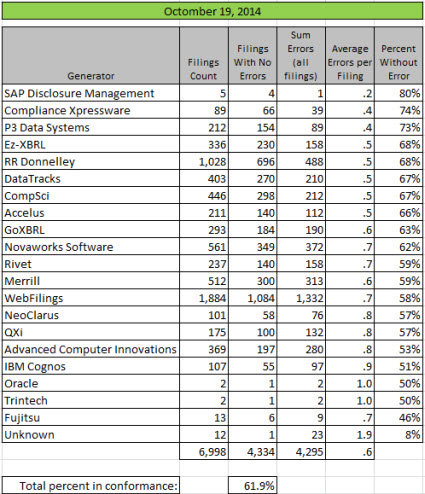

Back in April 2014 as part of the minimum criteria testing I was doing, I observed that the percentage of public company filings which conformed to all of the fundamental accounting concept relations was 25.6% (1711 filers).

Last month I pointed out that the percentage of public companies which conformed to all of these relations was 53.1% (3863 filers).

I ran the same test for the last filing of every public company which reports to the SEC today and the percentage that conform to all of the fundamental accounting concept relations is now at 61.9% (4334 filers). You can see the graphic below which breaks this information out by generator (filing agent or software used).

This rapid growth rate is expected to continue for three reasons:

- These relations between fundamental accounting concept relations is not really controversial and it is increasingly easy to understand and correct the errors.

- I have provided a substantial amount of information here which helps those who want to correct these issues. This recently added analysis shows that each of these tests can precisely detect not only nonconformance to these relations, but also generally the reason for nonconformance.

- I know of at least one commercial implementation of software which can be used to detect and therefore correct these issues, XBRL Cloud. This testing will appear on XBRL Cloud's Edgar Dashboard at some point.

If you look at the numbers below and compare them to the prior results you will see that pretty much every generator is improving. I pester software vendors to include this testing in their products to help them understand that their software can help external financial reporting managers avoid errors like these. But more importantly, I am trying to get software vendors to realize that this is only the tip of a much, much bigger iceberg. This is a digital disclosure checklist summary which I created several months ago. This shows you where things are headed.

These rules may seem annoying to software vendors. I can tell you two things. First, external financial reporting managers already have to comply with these rules. They are just doing so using time consuming and expensive manual processes. Second, automate these tasks by leveraging the XBRL-based structured information and you will provide something very useful: reducing the risk of noncompliance.

It is these rules which will make the quality of public company financial information submitted to the SEC to be at a level to make it safely, reliably, predictably usable by machine-based automated processes. If you don't understand digital financial reporting, the risk of becoming a relic of the past is increasing every day.

(Click image for larger view)If you don't want to become a relic of the past era of paper-based financial reporting, understand how digital financial reporting really works. Digital financial reporting is not only inevitable, it is imminent.

(Click image for larger view)If you don't want to become a relic of the past era of paper-based financial reporting, understand how digital financial reporting really works. Digital financial reporting is not only inevitable, it is imminent.

If you want to understand the moving parts and you can walk through an Excel macro, the prototype Excel application on a link at the bottom of this page can help you understand the important moving pieces.

Options for Dealing with Line Items that Bounce Around Income Statement

Those who study financial reporting might find this information rather interesting, both accountants who prepare financial statements and analysts who interpret those statements. You can find additional information in this analysis here. While this analysis focuses on "Income (Loss) from Equity Method Investments", these same ideas apply to other financial statement line items.

Here are the facts as I see and understand them. Not all economic entities have investments which are accounted for using the equity method, but if an entity does then they most likely report "Income (Loss) from Equity Method Investments". (This is another reference for equity method accounting.) The accounting standards state that this line item must be "reported as a single line item on the income statement." The SEC has additional information as to how this line item is reported in Reg S-X. The FASB Accounting Standards Codification (ASC) summarizes what they think Reg S-X says.

So, I challenge you to sort through all those reference materials to figure out exactly how the line item "Income (loss) from equity method investments" should be reported. In addition to reading through all that material, here is other information which I gathered:

- Multiple sources confirm that while the accounting literature states that this line item must be reported as a single and separate line item, WHERE it must be disclosed is not as clear.

- Some reference material states that reporting this line item with the other "separately reported items" such as discontinued operations and extraordinary items is the best practice.

- The US GAAP XBRL Taxonomy represents this line item in two ways: before taxes as a separate line item and after taxes as a separate line item.

- One highly regarded accountant that I talked to says that this should ONLY be reported and ALWAYS be reported after taxes because the line item can be used to manipulate the effective tax rate.

So, now let us see exactly how public companies report this information. Per an analysis of 9,679 XBRL-based financial filings, 1,048 or about 11% of economic entities reported this line item. Of that 1,048 this is where they reported that line item in their income statement:

- 624 entities (60%) reported the line item before tax directly as part of income (loss) from continuing operations before tax

- 110 entities (10%) reported the line item after tax

- 128 entities (12%) reported the line item as part of nonoperating income (expense)

- 20 entities (2%) reported the line item as part of revenues

- 10 entities (less than 1%) reported the line item as part of costs and expenses

- 8 entities (less than 1%) reported the line item as part of operating expenses

- 2 entities (less than 1%) reported the line item as a sibling to income tax expense (benefit)

- 60 entities (6%) created an extension concept and the line item rolls up to that extension concept

- 86 entities (8%) did something else which was not directly analyzed so exact placement is unknown

The first thing that I learned when I did this analysis is that I did not really understand that this variability was even allowed. Intuitively as a professional accountant, I was surprised. Other accountants I spoke with were likewise surprised that income (loss) from equity method investments could be included within revenues. And I am not saying that any of these reporting entities did anything wrong. I am simply making an observation.

These observations raise the following questions in my mind.

- What is the purpose of this line item bouncing around the income statement so much? Is there a legitimate reason why entities which use US GAAP have so much flexibility with this line item and not nearly the flexibility with other line items? (I have not analyzed 100% of all the fundamental accounting concepts yet, but this line item has the most variability that I have seen thus far.)

- Why exactly does this variability exist for this line item, but other line items do not have so much variability? Are the accounting standards ambiguous? Was it a conscious choice to allow this variability, or was it caused by a sloppily written accounting standard?

- What would happen if someone like the SEC or FASB would say, "This line item always goes after tax with other special reporting items, similar to discontinued operations and extraordinary items." Could the FASB or SEC do this? Should the FASB or SEC do this? Would analysts be happy about this or would they not like this to be forced into one slot on the income statement? I really don't know the appropriate answer to this question, but it seems to be a reasonable question.

- Chevron includes income (loss) from equity method investments within revenues, you can see this on their income statement. Chevron did not feel the need to create an extension concept for us-gaap:Revenues. Chevron clearly changed the definition of that concept by including that line item within revenues. Should Chevron have created an extension concept?

- Exxon did pretty much exactly the same thing Chevron did, including income (loss) from equity method investments as part of revenues, but then the DID create an extension concept to express revenues which included that concept. Who is right, Chevron or Exxon? Are both approaches allowable? Should both approaches be allowable, extend or not extend?

- Caterpillar reported income (loss) from equity method investments after tax, they created an extension concept cat:ProfitOfConsolidatedCompanies with the definition "Income (Loss) from Continuing Operations less Income Taxes and before Income (Loss) from Equity Method Investments" because they feel they moved income (loss) from equity method investments.

- Most of the other 110 who reported this information after tax did NOT create an extension concept.

What is the most interesting about this analysis is the fact that you can even perform this analysis and do so very effeciently and effectively. How? XBRL-enabled structured information. Each financial report alone and all financial reports collectively are data in a database which can be queried, sorted, sliced, diced. That has huge value.

Accountants work hard to represent information within a financial report. Sometimes the reference materials they have to work with are more ambiguous than one would prefer. One thing that is not ambiguous is what reporting entities actually do. External financial reporting managers pay people like Big 4 consultants a lot of money to sort through reporting issues. Smaller CPA firms have to likewise understand how to create financial reports. Actual financial reports are, in my view, the best resource for understanding how to create a financial report.

Certified public accountants have a duty and responsibility to improve the art of accounting. Improving the art of accounting enhances the profession of accounting. Certified public accountants have a duty to serve the public interest. The needs of both the reporting entities who create reports and the investors/analysts who use the reports must be balanced.

To employ the tools of XBRL-based digital financial reporting correctly, professional accountants need to learn the tool of digital financial reporting correctly. The rules are slightly different for human and machine-readable information than they are for human-only readable information the profession has been dealing with for 100 years. Making the change is not hard, it is just a little different. Machines are not smart, they are dumb. Machines only act smart if smart people make the machined serve their needs.

Personally, I don't understand all the answers, but I think I have a lot of very, very good questions.