BLOG: Digital Financial Reporting

This is a blog for information relating to digital financial reporting. This blog is basically my "lab notebook" for experimenting and learning about XBRL-based digital financial reporting. This is my brain storming platform. This is where I think out loud (i.e. publicly) about digital financial reporting. This information is for innovators and early adopters who are ushering in a new era of accounting, reporting, auditing, and analysis in a digital environment.

Much of the information contained in this blog is synthasized, summarized, condensed, better organized and articulated in my book XBRL for Dummies and in the chapters of Intelligent XBRL-based Digital Financial Reporting. If you have any questions, feel free to contact me.

Entries from October 9, 2011 - October 15, 2011

Handy Tool for Grabbing Taxonomy Information

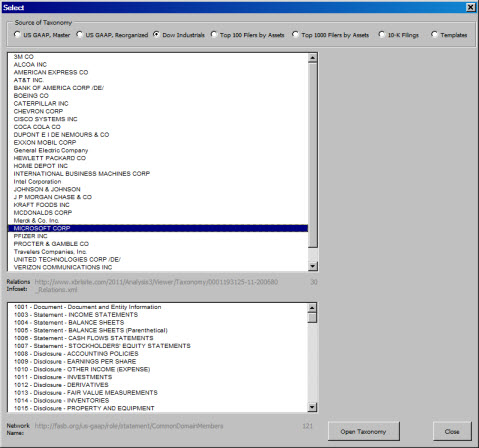

I created a handy little tool which can be used to grab taxonomy information. You can download the tool here. This is an Excel spreadsheet which has some macros.

The tool connects together lots of different sets of taxonomies which it will then load into either a tree view so you can look at the taxonomy or you can load the taxonomy information into the Excel spreadsheet.

These are the lists of taxonomies which the application points to:

- US GAAP Taxonomy "Master" (i.e. as modeled and released by the FASB, 56 commonly used networks)

- US GAAP Taxonomy "Optimized" (i.e. reorganized into a more logical form which is easier to use, total of 58 networks)

- Taxonomies of the 30 companies which make up the Dow Industrials

- Taxonomies of the top 100 SEC filers by total assets

- Taxonomies of the top 1000 SEC filers by total assets

- Taxonomies for all 10-Ks filed by the top 1000 companies (about 63 filings)

- Taxonomies for 9 "exemplars" (examples) for different forms of a balance sheet, income statement, and cash flow statement

This is just experimentation. The primary point I am trying to make is why have only one list of taxonomies when you could have many, many different lists which serve different purposes.

This application can be reverse engineered and modified to your heart's content. If you do fiddle with it and you create some interesting modified version of this, please send me a copy so I can check out your handy work.

Comparing XBRL Information 101: Lessons from the 30 Dow Industrial Companies

Here is some pretty basic information helpful in understanding how to compare SEC XBRL financial filings. This exercise also helps you see how constructing a taxonomy makes things easier, or harder, to compare.

Consider this list of the 30 Dow Industrial Companies. You could look through those filings one by one, reviewing the "Document Information" section for each of the 30 companies. But what I did was put all the document information sections for all 30 companies into one single file, which you can see here.

I will assume that you have some list of companies which you might want to compare. So lets start at the level of the section that you want to compare. Here we will focus on the "Document Information" section because it is simple, it is actually rather easy to compare, but it does point out the issues.

The first thing you will need to do is determine what level you want to do a comparison. Do you want to compare networks, tables, concepts, or some other "level"? I don't want to get into a discussion about levels right now, so let us just assume that we want to compare networks. So no problem, we just go get the network name of the section we want to compare. Right?

Well, not so fast. If you scan throught the list you will notice that every company created a unique network for its document information section. They did this because SEC filing rules tell them that they need to do this. It could have been the case that one specific network URI was used to identify document information for everyone such as the URI used by the DEI taxonomy which is (you can see it in the DEI presentation linkbase here):

http://xbrl.sec.gov/dei/role/document/DocumentInformation

But one unique document information network was not used, so you have to try something else.

OK, so try something else. The SEC requires that the document information be marked with the category "Document" (as compared to "Statement" and "Disclosure"). Well, that won't work either as Travelers (number 26) used the category "Statement" category, as opposed to "Document".

But the good news is that every one of the 30 DOW Industrials used the term "Document and Entity Information". So, we can use that, as I did, to identify the document information section. Will that same technique work for all SEC XBRL filings? I doubt it, may need to adjust the algorithm.

The next thing you will note is that of the 30 companies, every one extended the root node, there is no "dei:DocumentInformationAbstract" concept, every filer created their own extension concept. One, again Travelers, did an utterly strange thing. They used a [Domain] (dei:EntityDomain) as the root of that section. That clearly should not be allowed.

Next you will note that of the 30 companies, 6 companies used [Table]s and 24 companies did not use [Table]s. Of the 6which did use [Table]s; all used the "Legal Entity [Axis]" and the "Entity [Domain]" to indicate that the information of the document information relates to the consolidated entity as opposed to a parent holding company. As such, SEC EFM rules kick in and you need to imply that the other 24 are consolidated entities, rather than parent holding companies.

If you scan through the concept names you will see that no filer created extension concepts. (This does not include that root abstract element which would never report information, it is only there to help organize the section. So while each filer reported different concepts, this information is quite easy to compare.

There are no real relations between the concepts other than the information is document or entity information. As such, there are no business rules we need to make sure are valid.

This same general approach can be utilized for comparing any information in SEC XBRL financial filings:

- Get your list (in this case, my list was the 30 Dow Industrials companies)

- Decide what section you want to compare (in my case I chose the document information network)

- Resolve the differences between the structure of information (if there is not an explicit [Table], there is an implied table with the legal entity [Axis] which has the value of dei:EntityDomain or consolidated entity)

- Compare concepts (in our case this was easy as there were no extension concepts)

- Compare business rules (in our case there were no business rules to deal with as there were no computation type relations)

Easy enough steps, harder to apply because of inconsistencies in SEC XBRL financial filings, but quite doable. To make this easier, reduce the inconsistencies in the system.

Insuring your SEC XBRL Financial Filing is Correct Effectiently and Effectively

Many accountants and auditors find the process of verifying that SEC XBRL financial filings are correct rather challenging. I certainly understand this being a CPA and ex-auditor and having struggled for years trying to make sure the XBRL I was creating was correct with either no software or early XBRL software tools which were quite technical in nature and rather hard to use.

While software applications for enabling such verification of SEC XBRL financial filings is still rather immature, the software is in fact maturing and verification processes and techniques used in the past are less appropriate today.

A big part of the challenge of making sure your SEC XBRL financial filings is correct is your fundamental philosophy. First off, what exactly does "correct" mean? I define correct as:

- HTML and XBRL convey the same message

- Integrity: each piece is correct and all the pieces fit together

- Clear and appropriate business meaning/semantics

- Consistency with peers

- Consistency between current and prior periods

- Justifiable extension concepts

- Appropriate rendering

- Usable by analysts

The second challenge is to understand how do you know that everything is correct? Everything which should be there is there, nothing which should not be there is included, and everything which is stated is accurate?

The first tip, forget about the XBRL technical syntax.

Forget about XBRL Technical Syntax

Should the XBRL technical syntax of your filing be correct? Absolutely. If your software application cannot do this for you so you don't have to worry about it then you likely need better software.

Should your ampersands within an XBRL footnote be double escaped? Of course you ask, "What is this guy talking about?" That is precisely my point. The Edgar Filing Manual (EFM) says that you need to double escape your ampersands. Are you going to check for that? Of course not. Software should not let you NOT comply with that rule. Verifying these sorts of things can be 100% automated within software, business users need not deal with this. Besides, the SEC will not accept incorrect XBRL technical syntax, their submission validation process makes sure this is the case.

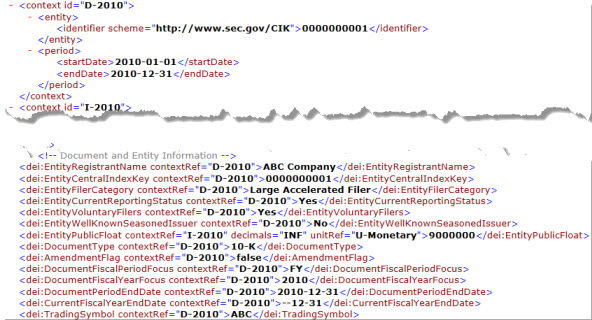

Another reason you should forget about XBRL technical syntax is this: Can you actually read XBRL technical syntax? Should you be able to? Some people can. More people think they can but really cannot. Here you go, give it a try:

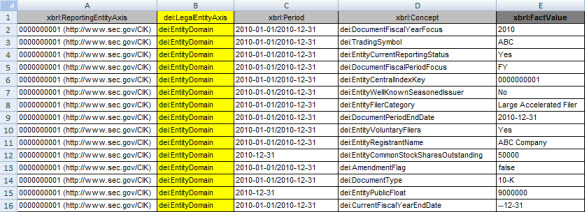

Here is exactly the same information rendered as an Excel spreadsheet, I call this a fact table:

A fact table shows all the facts and all the characteristics of each reported fact. Did I change the meaning of the information by moving it from the XBRL syntax to the Excel syntax? Certainly not. Which is easier to read, the XBRL or the Excel? Notice that there is no syntax information at all in the Excel such as the context ID. Clearly you need additional information such as the units and decimal information for numeric values, but the point here is that it is the semantics which are important, not the syntax.

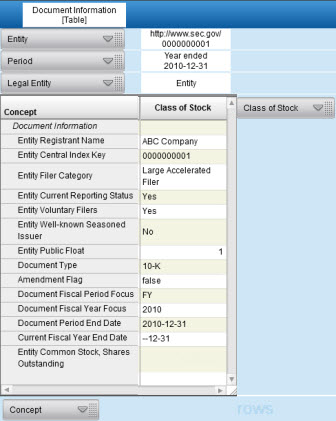

Taking this one step further, here is exactly the same information which was shown in the Excel fact table shown again, this time rendered within an XBRL viewer (in this case XBRL Cloud's XBRL viewer application):

"What do you mean, same information?", you ask. Yes, it is the same information. The information from the Excel table, the fact table, contains the business semantics, the characteristics of the facts being communicated by the SEC XBRl financial filing. All the rendering application does is the same thing that an Excel pivot table does, it renderings the information into a form which is consumable by business users.

If you look at the business meaning of information contained in an XBRL instance, it might look like the Excel fact table shown above or it might look like the more human friendly rendering. In fact you could and should have both views. Both the fact table and the rendering communicate the same information, but the different forms help you achieve different things. Does how the information is rendered change the business meaning of the information? Certainly not.

I think that while you would probably acknowledge that some software applications are better than others at helping the user to see the business meaning, it is not the case that whether information is rendered in the form of a fact table or in a more human readable form; rendering the information does not change the business meaning.

Reasons Why Syntax Doesn't Matter

I think it would be easy to agree that taking information which is in the XBRL format and putting that information into some other syntax such as Excel spreadsheet, a database, some other form of XML does NOT change the meaning of the information. In fact, it certainly should not because that is a fundamental characteristic of XBRL; the ability to exchange the information between different business systems.

So while the syntax changes when the information contained in an XBRL instance and taxonomy moves from the form of an XBRL instance, into Excel and/or into the form of a database application or some other format; the meaning of the information (the semantics of the information) does not change.

Further, there are different ways to express exactly the same business meaning using the XBRL syntax.

Consider, for example, that the SEC has rules relating to expressing, which reported information relates to the legal entity "consolidated entity". In essence, the EFM states that unless you state otherwise, the legal entity is assumed to be the "consolidated entity". The EFM states something to the affect that by creating an [Axis] and a [Member] for that [Axis], the information expressed in an XBRL instance and its XBRL taxonomy relates to the "consolidated entity". You use the [Axis] "dei:LegalEntityAxis" and the [Member] "dei:EntityDomain". Or, you could also NOT physically provide any legal entity [Axis] nor the [Member] (i.e. you do not create a [Table]). Therefore, no legal entity [Axis] is provided and therefore the legal entity is assumed to be or implied to be the consolidated entity.

In essence, you can either explicitly state the legal entity or you can imply the legal entity per the SEC EFM rules.

Does your choice of which approach you use, using or not using the XBRL syntax of a [Table], impact the meaning of the information? I think that you would agree that it clearly does NOT impact the meaning of your information. Here is an example of what I am talking about, Dow Chemical Company does NOT use a [Table] and Apple DOES use a [Table] to express exactly the same information:

- Dow Chemical Company: SEC Viewer | Taxonomy

- Apple: SEC Viewer | Taxonomy

But wait, there is more! You can take the explicit versus implicit representation of the legal entity one step further.

In the XBRL syntax, or more accurately the XBRL Dimensions syntax, there is the notion of a "dimension default". If the dimension default is indicated in an XBRL taxonomy; that dimension would physically not exist within the context for that fact within an XBRL instance. So, does the business semantics of the information change between the options you choose to use the "dimension default" or not use the "dimension default"? Clearly not.

Now, under SEC reporting rules, you are always required to use a dimension default. However, if you do use the dimension default that dimension and the default value of that dimension (a [Domain] or a [Member]) do not physically exist within the context of the XBRL instance. Does the fact that the syntax rules of XBRL which states that the [Axis] and [Member] in our case the legal entity axis and the value "consolidated entity" expressed using "dei:LegalEntityAxis" and "dei:EntityDomain", but in this case not physically there because of the technical rules of the XBRL syntax; does this change the business meaning of the information? Clearly not.

Focus on Business Semantics

When you review an SEC XBRL financial filing, do you care that any of the following core financial semantics (meaning) is appropriately articulated:

- Balance sheet reports assets

- Balance sheet reports liabilities and equity

- Balance sheet reports equity

- Balance sheet balances

- Balance sheet foots

- Cash flow statement reports net cash flow

- Net cash flow foots

- Income statement reports net income (loss)

- Income statement foots

- If a classified balance sheet is presented, the balance sheet reports current assets and current liabilities

Now we are talking! This is both understandable to an accountant and/or auditor who is checking to be sure the information is properly articulated and it is also part of the characteristics of a quality SEC XBRL financial filing. And this is just the tip of the iceberg. Every aspect of an SEC XBRL financial filing can be evaluated in the same way: does it exist, does it foot, does it cross cast, is it the correct concept, are all the pieces correct, do the pieces tie together properly, etc.

Bottom Line

Clearly it is important for the XBRL technical syntax to be correct. Software applications can automatically check to be sure that your escaped XHTML has property double escaped those ampersands. And your software should not bother you with these details, of which there are thousands and thousands.

Accountants and auditors need not consider the XBRL technical syntax when trying to determine if an SEC XBRL financial filing is correct for two primary reasons:

- You don't understand the XBRL technical syntax, you likely never will understand the XBRL technical syntax, and you never really needed to understand the XBRL technical syntax in the first place. You will likely always be using the information contained within an XBRL instance and XBRL taxonomy from within some software application built for business users. The software will put the information into a form which allows you to be sure the information is articulated correctly.

- It is far more effective and efficient to review information in a form which is easy for you to use and understand. It is the business semantics which you care about, not the XBRL technical syntax. Focusing on the XBRL technical syntax is a waste of time and money.

If your software does not both properly hide the unimportant XBRL technical syntax from you and expose the imporant business meaning of information to you in a form what is useful to you, then start looking for better software.

Workflow Involved when Creating a Financial Statement

In a prior blog post I pointed out that creating a financial statement is a collaboration between many parties which exist both within your organization and some of which are external to your organization.

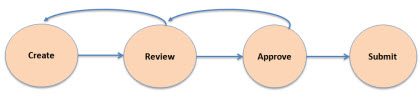

In this blog post I want to point out that there is a workflow which exists when creating a financial statement. Here is a very simplified workflow: create, review, approve, submit.

Clearly one can dig deeper into the many, many details of the workflow of creating a financial statement. The point here though is to simply point out that one should be thinking about workflow when considering software for creating SEC XBRL financial filings.

Clearly one can dig deeper into the many, many details of the workflow of creating a financial statement. The point here though is to simply point out that one should be thinking about workflow when considering software for creating SEC XBRL financial filings.

Further, workflow can be determined by the fundamental approach one chooses for getting their SEC XBRL financial filing created. Popular categories of approaches (which are covered in chapter 11 of XBRL for Dummies) include:

- Bolt on: You basically "bolt on" another process for generating the XBRL to an existing process of creating the Word and HTML versions of your SEC filing. Typically one might purchase an additional software product to generate your XBRL output.

- Out source: Outsourcing is really somewhat of a bolt on approach except that rather than purchasing software which adds the additional needed functionality of generating XBRL, you out source the entire process.

- Integrated: Integrating the creation of the Word, HTML, and XBRL formats into one process is another approach to getting that XBRL generated. This generally involves purchasing new software which offers XBRL generation or updating to a new version of an existing software product which you use which offers the feature of XBRL output.

- "Roll your own" solution: A type of integrated approach is for you to "roll your own" solution by either creating internal systems which generate XBRL or somehow enhancing the functionality of a third party software product which you use. For example, this article discusses United Technologies use of XBRL.

If you were around when the PC was first introduced, you will recall that initially PCs had a character-based interface. Think "DOS". That all changed with the introduction of the graphical user interface by Apple on its first Mac. Not everyone believed that the graphical user interface provided an improvement over the DOS character based interface. But Apple proved the graphical user interface and the user interface paradigm shifted.

A similar paradigm shift will occur with SEC XBRL financial filing software. If you really consider workflow; the common approaches used today where someone bolts on an additional process or outsourcing the process of generating the required XBRL does little to improve the overall financial statement creation process. That is why accountants see little value in XBRL today.

When work flow is considered and appropriate software is created the value accountants will see from XBRL and what XBRL enables will change. When will this change take place? In my view the change is already occurring slowly but surely. The pace will become more rapid over next year, I predict.

Further, I predict that accountants will be using XBRL enabled semantic, structured, model-based authoring software products for creating financial statements whether they need to submit XBRL to some regulator or bank, or not. Why? Because the workflow enabled by technologies such as XBRL will enable more effecient and effective processes.