BLOG: Digital Financial Reporting

This is a blog for information relating to digital financial reporting. This blog is basically my "lab notebook" for experimenting and learning about XBRL-based digital financial reporting. This is my brain storming platform. This is where I think out loud (i.e. publicly) about digital financial reporting. This information is for innovators and early adopters who are ushering in a new era of accounting, reporting, auditing, and analysis in a digital environment.

Much of the information contained in this blog is synthasized, summarized, condensed, better organized and articulated in my book XBRL for Dummies and in the chapters of Intelligent XBRL-based Digital Financial Reporting. If you have any questions, feel free to contact me.

Entries in comparability (4)

Issues in Comparing SEC XBRL Filings

It is getting a little easier to communicate issues relating to XBRL reports. The biggest problem in doing this is that most people don't know how to "read" XBRL. But as software applications become available being able to understand these sorts of issues will become easier.

There are a number of issues relating to doing basic comparisons of SEC XBRL filings. I am fortunate enough to have been dinking around with XBRL for over 12 years now, I can pretty much look at XBRL instances and taxonomies and figure most things out. During this time I have built a multitude of software applications to help me read XBRL easier and communicate information to others. I have taken that up a notch, combining about 10 different software tools into one tool which I call my XBRL audit or query or analysis tool.

That XBRL audit/query/analysis tool can generate a report which focuses on networks (i.e. extended links), hypercubes (i.e. [Table]s in SEC XBRL filings) and dimensions (i.e. [Axis] in SEC XBRL filings).

Here are six different reports which I will use to make a few points. The analysis reports show different characteristics. The focus here is comparability of the XBRL instance information. I will look at how networks, hypercubes (i.e. called [Table]s in SEC filings), and dimensions (i.e. called [Axis] in SEC XBRL filings) impact comparability. So here are the reports with a bit of information about each report.

- Analysis of Apple SEC filing: Actual SEC filing. Note that all concepts reported are modeled within [Table]s, in the case of this filing, the [Table]s are always the same, "Statement [Table]".

- Analysis of Heinz SEC filing: Actual SEC filing. Note that not all concepts reported are modeled withn a [Table], you will see that many networks say "xbrl:No [Table] (None)" in the column headed "[Table] (i.e. Hypercube).

- Analysis of SEC Model Filing I created: Test SEC filing I created to make some points. Note that every concept is modeled within a [Table] which is similar to the Apple filing, but in my case every [Table] has a unique name which identifies the concepts in the [Table], rather than using "Statement [Table]" for every [Table]/hypercube.

- Analysis of Comparison Example ABC Company: Prototype GAAP filing created to test comparability. This was build to be comparable with the XYZ Company and QQQ Company filings below. Note that all three filings use [Table]s (which are called Fact Groups as they follow the straw man implementation of the Business Reporting Logical Model (BRLM).

- Analysis of Comparison Example XYZ Company: Prototype GAAP filings, built to be comparable with ABC Company above.

- Analysis of Comparison Example QQQ Company: Prototype GAAP filings, built to be comparable with ABC Company above.

To start off let me say that this is not about my personal view as to what should or should not be comparable, that is not the point. The point here is this: if you want comparability, there are ways to get it and there are ways to make comparability more difficult to achieve.

You may want to start off doing two things. First, scan each of the reports which I have linked to noting what you have in each report. Then, compare the reports looking for similarities and differences between the reports. If you are really interested in this and want to do some extra credit work, note that each of the analysis reports links to the actual XBRL instance. Take the actual XBRL instances and try to compare them in some XBRL analysis tool. Try to compare 1, 2, and 3. Then try and compare 4, 5, and 6.

OK, so to my points (it helps to open all 6 reports above in your browser and bounce between them as you read this):

- All information is "dimensional", don't confuse syntax and semantics. A lot of people freak out when you talk about XBRL and dimensions. The truth is that all information in XBRL is dimensional. The dimensions are expressed using different syntax options, but the information is dimensional. If you look at the column headed "[Axis] (i.e. Dimension)", you will always see three dimensions for every "chunk" (sets) of information: xbrl:Concept [Axis], xbrl:Entity [Axis], and xbrl:Period [Axis]. Other [Axis] may be added by taxonomy creators, or not.

- Comparability is impacted by what [Axis] you have and what level the [Axis] was defined. If different hypercubes have different [Axis], the information will not be seen as comparable by software. There is a higher probability of comparability if an [Axis] is defined at the "GAAP" level than at the company/filer level.

- Comparability is impacted by networks and hypercubes [Table]s. Just as with the [Axis], comparability is impacted by networks and hypercubes; and the level that networks and hypercubes are defined impact comparability. For example, note the Apple and Heinz filings, seeing that every network was defined by the filer. Therefore, no networks in either the Apple or Heinz filing are the same. If you look at the Model SEC filing, note that there are (illegally, the SEC does not allow this) a few US GAAP Taxonomy defined networks. If Apple and Heinz had both, say, used the US GAAP Taxonomy network for the "balance sheet", then one could get the "balance sheet" for both Apple and Heinz. If you contrast that to the ABC Company, XYC Company, and QQQ Company reports you will see that all but one network is the same in all three reports. The same deal with hypercubes. If one uses no hypercubes or uses hypercubes which are all the same then basically the hypercubes [Table]s are useless. But, if each hypercube is unique, the hypercubes can be used as a basis of comparison. In filings 4, 5, and 6 all the hypercubes are unique and one could use the networks OR the hypercubes as the basis for comparison. (Except for the last network (QA, Part 1: Variance Analysis) and hypercube (Variance Analysis, Gross Profit [Fact Group]) which were defined at the company/filer level, and therefore is harder to compare as a computer will not understand them to be the same.

- If networks or hypercubes are not the fundamental basis for comparison, what is?Suppose you want to go grab all the accounting policies for a filing. Or any set of anything really. Try to find those "chunks" (sets) of information in any one SEC XBRL filing, or even more useful in any two SEC XBRL filings so you can actually do a comparison. It does not appear to be possible at the network level. [Table]s are not comparable either. Comparisons of individual concepts is useful, but too detailed and the concepts are best understood within some context (i.e. some set of information, like a balance sheet).

Some people say that you can throw software at the issues shown above and let computers sort all this out. That can happen to a degree. For example, clearly you can write a program to go find "Assets" and "LiabilitiesAndEquity" and there is a good chance you found the balance sheet. But maybe not, you may have found a segment breakdown. Some things are possible using brute force and software, but one will still have to define the sets somehow.

Particularly for less sophistocated users trying to glean information from these filings, it would be better to use networks, hypercubes, and dimensions to define information rather than fight with them. The first three XBRL instances show the hard way, the last three show an easier way.

Which approach do you feel is best?

Basic Comparison Example of SEC XBRL Filings Shows Issues Relating to Comparability

The Basic Comparison, SEC XBRL Filing exampleshows issues relating to comparing SEC XBRL filings. If you understand how to read the XBRL instances and XBRL taxonomies or if you dig into the Measure Relations and Fact Groups (Fact Tables), comparability issues jump out at you.

Now granted, the issues will be better seen within a software application actually trying to do a comparison; but I cannot show such an application currently.

Don't be fooled by the simplicity of this example. It is simple, but it is not simplistic. The information in the XBRL taxonomy and XBRL instance is concise, but it serves its purpose.

For example, imagine that you want to compare the accounting policies of these three basic SEC XBRL type filings. How would you do this? First off, you might try and find the extended link which contains the accounting policies, using that to grab all the accounting policies. Well, that will not work. EFM rules state that company extensions cannot use extended links from the US GAAP Taxonomy. There is an extended link, but each filer needs to create their own extended link. Look closely at the Measure Relations of the ABC Company, XYZ Company, and QQQ Company and you will see what I mean. So, you cannot use extended links for comparisons at all.

OK, the next level down in the taxonomy after the extended link is the [Table]. Just grab the Accounting Policies [Table], use that as the basis for comparison. This is a great idea, but that will not work either. The reason is that there is no Accounting Policies [Table] in the US GAAP Taxonomy. Now, I created one in these three example filings, but although they have the same name, they are from different namespaces (abc:, xyz:, qqq:); they are not the same and will not be seen as the same by software applications. Another way to understand this is to look at the Nonmonetary Transactions, by Type [Table]. Now that [Table] is comparable as (a) it does exist in the US GAAP Taxonomy, and (b) each filer used that [Table]. A rather simple program can be written to get that [Table], all the concepts in that [Table] (as that is clearly defined in the definition linkbase) and you have your comparison.

But you don't have that [Table] to use. You may think that you do because in this example you could ignore the namespace prefix but then you would be missing the point here. Although I named the elements the same in each taxonomy, there is nothing which will ensure that SEC XBRL filers will do this in their filings. So, perhaps there is some concept that everyone uses in their taxonomy, use that and the presentation relations to find all the accounting policies. If you go look at real SEC XBRL filings you will see that that will not work.

The bottom line here is that there is no dependable way to do a comparison of accounting policies. You could spend time and money creating a pretty good software algorithm, but why not make the problem go away so you don't have to spend the time and money to write that algorithm. Just add an Accounting Policies [Table], require that everyone use that [Table], then compatibility can be easy. Same deal for other portions of the taxonomy. This is not to say that everything needs to be required, but base areas such as the accounting policies seem to be something everyone should really have. Same for the balance sheet, income statement, cash flow statement, other specific disclosures, and other areas. What might be contained in those [Table]s may be different, but the place to look in each SEC XBRL filing would be the same. How else would comparability be achieved?

This is just one example, there are many other clues in this basic example. As is said, the proof will be in the pudding: in actual and useful comparability. Where the comparability will exist is a decision for the financial reporting domain. But clearly there should be some comparability at some level.

Have a look at the Basic Comparison example and see what you come up with. Or even better, load these three simple SEC XBRL filings into your favorite comparison tool and see what you come up with.

Business Reporting Logical Model Enhances Comparability and Interoperability

Another thing that the Business Reporting Logical Model does is enhance comparability and interoperability. Or to be more precise, the Business Reporting Logical Model minimizes the effort required to achieve comparability and interoperability. It opens the possibility of a business domain to create comparability, should they desire to do so. Interoperability means easier to use software and less costly software for business users.

Here is why.

Comparability

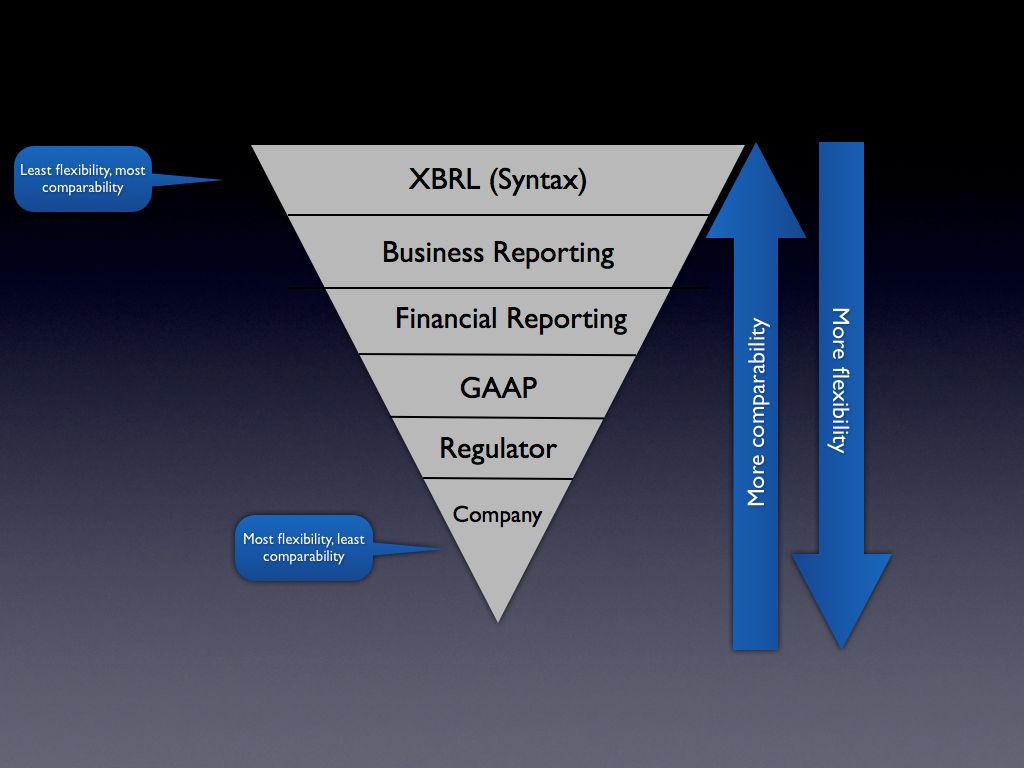

(Here is a link to a PDF of this graphic.)

Today, there is no logical model below the XBRL syntax level. The only model any business domain has to work with is the XBRL syntax or some model they create. Creating that model and all the infrastructure to enforce that model takes time and costs money.

Or, another way of looking at this is that each company desiring to use XBRL for, say, financial reporting could create their own model using XBRL. That model could be 100% XBRL compliant (i.e. comply with the global standard). Each company would have to deal with all the "stuff" in the middle such as which GAAP (accounting standards they would use), create their own XBRL taxonomy, and so forth.

The "middle ground" needs to be created. The US GAAP Taxonomy created some of this middle ground. You can see that middle ground in the US GAAP Taxonomy Architecture. But, the US GAAP Taxonomy is not enough. That is why the SEC had to create a boatload of additional EDGAR XBRL Validation tests (see this list of errors, here is the test suite). Of course, the SEC would probably never want XBRL International to deal with 100% that that specific regulator needs to deal with, nor would XBRL International members do that; it would be like everyone agreeing to do business reporting exactly like the SEC does it, that would become the XBRL standard.

Business information exchange is a balancing act. Where agreement is achieved has ramifications for business users. Too much flexibility has its issues, too much comparability (or requiring things too high in the stack) has its issues. Where comparability exists within the "stack" (the diagram above) is up to the business domain's implementation of XBRL. XBRL itself does not control this. How XBRL is used does.

Interoperability

There is another piece to this puzzle. XBRL is a standard. What a system needs to make business information exchange work properly, it seems to me, is a protocol. There is a difference between a standard and a protocol. A difference worth understanding. Erez Ascher (Ascher Consulting & Development) articulates the difference between a protocol and a standard as:

- A protocol is a series of prescribed steps to be taken, usually in order to allow for the coordinated action of multiple parties. In the world of computers, protocols are used to allow different computers and/or software applications to work and communicate with one another. Because computer protocols are usually formalized, many people consider protocols to be standards. However, such is not actually the case.

- Standards are simply agreed-upon models for comparison, such as the meter and the gram. In the world of computers, standards are often used to define syntactic or other rule sets, and occasionally protocols, that are used as a basis for comparison. Some good examples include ANSI SQL, used to compare derivations of the SQL database query language, and ANSI C, used to compare derivations of the C programming language.

In other words, it seems to me that protocols can be standards, but standards may not contain all that is necessary to "allow different computers and/or software applications to work and communicate with one another". Therefore, every business system, such as the SEC XBRL filings system, must add "stuff" to XBRL to turn the standard into a protocol it seems. For every system to have to do this is both inefficient and ineffective because you really don't get cross business system interoperability. What you get is what we have today - many point solutions or one-to-one integrations.

So not only does the Business Reporting Logical Model enhance comparability, it also enhances interoperability. The Business Reporting Logical Model can provide the pieces which can turn the XBRL standard syntax into a business reporting protocol. I am not sure if it is all the pieces, time will tell. But I am sure XBRL alone is not enough to give business users what they need from XBRL.

The Bigger Picture - Financial Reporting in the Age of the Semantic Web

There is a bigger picture here. Consider this blog post titled "Why the Semantic Web Will Fail". The post is pretty good, but what is really interesting are the comments to the post. The way I read that post and all the comments is that the Semantic Web is inevitable, but no one knows when it will arrive.

I contend that the Semantic Web is already here. The US Securities and Exchange Commission (every US public company financial in XBRL by July 2011), XBRL US (US GAAP Taxonomy), Tokyo Stock Exchange, Japan Financial Services Agency, Korean Stock Exchange, China Securities Regulatory Commission and Shenzhen Stock Exchange, Japan's EDINET, the Commission of European Banking Supervisors, the US Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, the International Accounting Standards Board (IFRS, standardized financial reporting meta data expressed in the XBRL syntax) among others have already created pieces of it for financial reporting. The US SEC, Japan FSA, and IASCF are already reconciling their implementations of the XBRL standard to make them more interoperable. The Business Reporting Logical Model will make it so others don't have to go through this reconciliation process.

Is XBRL perfect? Certainly not. But XBRL is not RDF/OWL. Who cares, both XBRL and RDF/OWL are just syntax. On can convert from one syntax to another easy enough. The hard part, agreeing on the meta data and getting vendors to support the idea, is done (for US GAAP and IFRS). The IASB started on IFRS in the 1970's, even before the Internet existed. Most countries have either switched to IFRS already or will. Even if they all don't (i.e. the US will converge, but may not convert), reconciling US GAAP to IFRS is not that much of a challenge really. Oracle, SAP, and IBM all support XBRL within their software.

Maybe I am wrong, but it seems to me that a better question might be "When will others catch up to how the financial reporting business domain has embraced the Semantic Web?" That may by an over statement, financial reporting has a ways to go. The Business Reporting Logical Model will help others get into the Semantic Web easier than the early pioneers.

How did XBRL International get to where it is? Back in 2003 Joan Starr wrote an article Information politics: The story of an emerging metadata standard. Here is the article's abstract:

Information politics: The story of an emerging metadata standard by Joan Starr

This is the story of how one commercial metadata standard — XBRL, or Extensible Business Reporting Language — has attracted the participation and support of some of the world’s most powerful public and private organizations. It begins with a look at the nature and use of financial information in today's Internet-enabled environment and discusses three information use patterns: Transaction, retrieval, and reporting. While numerous, sometimes competing standards have been developed for transaction information, XBRL alone has emerged to address reporting formats. Today, the XBRL specification has wide support across the accounting, financial, and regulatory communities. This has come about largely through the efforts of the standards’ governing board, which has pursued a strategy of careful definition of market scope, deliberate courtship of important allies, and establishment of a culture of aggressive outreach for members. The results are impressive. Members of the organization are now positioned to take greatest advantage of a number of new entrepreneurial opportunities that have been created by the organization. Additionally, some participants are now representing the XBRL metadata standard as a key tool for the restoration of public confidence in the scandal-rocked accounting and investment industries. This may create a serious problem for researchers and investors as unaudited financial statements formatted in XBRL proliferate on the Web sites of corporations anxious to demonstrate a commitment to what some are calling "the new transparency."

XBRL seems to have achieved the right mix of technical and business participation. While what the technical people did was very good and very important, I think that what the business people who participated in XBRL created was perhaps even more important. Business users of XBRL should try and understand and push for the Business Reporting Logical Model to be standardized within XBRL International.

This will provide the flexibility where flexibility is needed, but also the things needed for a protocol to work well, be effective, and be efficient. Having every implementation of XBRL undertake this task will hurt XBRL, making comparability of XBRL based information more challenging and interoperability of XBRL software and different implementations near impossible.

So that is what I see. How do you see it?

A Thought Experiment: Understanding XBRL Instances

(Albert Einstein was famous for the thought experiments he used to explain complex situations using simple stories. The purpose of this thought experiment is to help you better understand how XBRL instances actually work. The first thing the experiment shows you is the important pieces impacting the usability of XBRL instances. The second important aspect the thought experiment shows is that the way business users implement XBRL determines the results received from that XBRL-based information.)

In chapter 18 of my book XBRL for Dummies (which is now shipping!) I use a thought experiment to help you see what it takes to make XBRL achieve what many business users tend to want from XBRL which is to reuse the information within some automated process. Now, if you don't care about information reuse, then you may not care about these sorts of things. But if you do, what does it really take to achieve reuse of information?

Let's look at financial reporting as an example.

Again, the ultimate goal you're trying to achieve with XBRL is to automate some process. You many times reap significant benefits from realizing this goal. I am NOT saying that all business processes are automatable or that all processes should be automated. What processes to automate and where to include humans is up to those creating business processes.

But, errors, inconsistencies, ambiguities, and other such factors sometimes keep processes that can and should be automated from being automated, requiring human intervention to execute the process. This is not because you want to involve humans; it's because you haveto involve humans due to errors, inconsistencies, ambiguities, and other factors. The humans need to resolve the errors, inconsistencies, ambiguities, and other factors which prevent the automation of the process. Again, this is should you choose to automate some process.

Think of the Web. Imagine that every company in the world created quarterly and annual financial information and put that information in an XBRL instance on its Web site. Forget about whether you could get every company to make this information available or even if they should make it available. (It's a thought experiment, so just play along.) Imagine that you wanted to analyze all that information for some purpose.

Here are the challenges you would face:

- Finding the XBRL instances: You need to find those XBRL instances. How do you do that? You have two possibilities: push and pull. Push means that in some way, perhaps via an RSS feed that pushes this information to you, you're made aware of each of the XBRL instances. Pull, for example, is when you discover the XBRL instances via a search engine and then pull the information to where you can use it. But somehow you need to discover the complete set of XBRL instances you need for your analysis. For our experiment, say that a search engine finds all the right XBRL instances, and only the right XBRL instances, and makes them available to you. So, you have all the information.

- Having comparable concepts and relations: You have all the XBRL instances, delivered somehow by your search engine. If each XBRL instance uses a different XBRL taxonomy, comparisons between XBRL instances are more challenging. You can still compare information by mapping each company's XBRL taxonomy to an XBRL taxonomy you create as a master comparison taxonomy. You'd have to create this mapping for every XBRL instance in this case. An alternative is that every company agrees to use the same XBRL taxonomy. Say they did that; in fact, say every company used the IFRS XBRL taxonomy for financial reporting. But now say that companies are allowed to extend the base IFRS XBRL taxonomy. Thus, in effect, now each company is using a unique XBRL taxonomy, and you're back to having different concepts and relations again. However, for this experiment, say that extension isn't allowed, so you have perfect comparability.

- Putting all the instances together: You have a complete set of XBRL instances, and you have only one XBRL taxonomy with no extensions allowed, so you have perfect comparability at the XBRL taxonomy level. You now put all the XBRL instances together into one massive, combined XBRL instance containing all information for all companies in the world. Easy enough: After all, XBRL's purpose is to achieve this sort of result.

- Resolving entity conflicts: You pull all the XBRL information together into one big XBRL instance. Do you have conflicting contexts? Theoretically, no. Each company reports only its information, not the information of others. Each context should be of the reporting company; therefore, each company provides its own entity identifier within its context. Again, say that every company had one and only one unique identifier, and that every company can be effectively uniquely identified and identified only once (meaning no duplication). So, we can have no entity conflicts.

- Dealing with period conflicts: What if companies had different fiscal year-ends? We all use the same calendar, right? That is because the world standardized on one calendar for the most part. (It was not always that way, however.) Well, in the real world run into the situation where different companies use different fiscal year-ends, not ending on the same calendar date. A fiscal year is some financial period (say July 1 through June 30); it may not be a calendar year. Further, many retailers use a 52/53 week year end. Let's ignore this. For this thought experiment, say that every company has the exact same fiscal year-end, which is December 31.

- Handling unit conflicts: Different countries use different currencies; therefore all this information is reported in all sorts of different units, from U.S. Dollars, to UK Pounds, the Euro, Japanese Yen, or Chinese Renminbi, or something else. But say that you can convert to some standard currency - say, the Euro for this comparison. For the sake of this experiment, assume that this conversion was done in real time and accurately. As such, you have no unit conflicts.

- Agreeing on standard metadata: For this thought experiment, say that you've standardized industry sector identifiers (identifying companies as being a bank, an airline, in retail, and so on), geographic areas (used to differentiate operations in Europe, Asia, and so on), standardized entity information for identifying parent companies as opposed to a subsidiary, and any other thing that can cause a comparability issue. Your meta data is perfect. As such, you can identify parent companies and which industry sector a company is in, you can differentiate between budgeted and actual information with XBRL instances, and so on. You use XBRL Dimensions to construct this dimensional information, which is totally standardized across all companies reporting information. (Remember, it's a thought experiment. Einstein pretended he was riding on a light beam, for Pete's sake!) So, all this meta data is standardized enabling comparability.

- Coming up with an analysis interface: You have a huge set of information, all in XBRL, for all the companies in the world. All the companies are uniquely identified. All the companies use exactly the same XBRL taxonomy to report their information, and no extensions are allowed. Everyone uses the same fiscal period for reporting their information. All the numeric values use one standard currency. All parent companies are clearly identified, and all actual information is differentiated from any budgeted information. Basically, everything is perfect: You've achieved information comparability nirvana. You have an easy-to-use business-user interface that's even better than the popular Apple iPhone in terms of usability. It's the perfect business-user application! Isn't life grand!!!

So what is your point, you ask?

One point is that reality can be messy. Reality isn't perfect. All the issues pointed out in the list do exist. These issues are real issues which XBRL has to deal with.

Another point is that many things are possible technically but maybe not politically. Technically, you can do everything we mention as we walk through the issues to resolve each issue in some way with XBRL. In fact, that is typically quite easy. The harder part is actually doing it - for example, agreeing on a standard format like XBRL, standardizing how entities are uniquely identified, standardizing on industry sectors and geographic areas, and so on.

Some agreements are already being reached in the area of financial reporting. XBRL itself is a step in that direction. IFRS is another step. But financial reporting is only one business domain. There are many, many other business domains. Some are easier to create comparability within than others. Some desire comparability, others do not. The desire for compatibly is the responsibility of the domain. Technically, XBRL can deliver comparability, should some business domain desire it and work to create it.

This experiment points out the major moving parts of working with XBRL instances. I use financial reporting only as an example in our thought experiment. Each different business domain will decide how to employ the technology of XBRL within their unique domain.